Search results

-

On the 3 May 2024 Stuart from The AIDS Memorial (Instagram) contacted me to say that a photo of my dear friend Andrea Philippe Regard would be featured in the ‘Live to Tell’ segment of Madonna’s ‘Celebration’ concert being held in Rio on 5 May. The Aids Memorial was a direct inspiration for the Brighton AIDS Memorial, so Andrea’s inclusion in the show in his home country was both a wonderful surprise and an honour. Andrea loved Madonna and when we chatted in my café, ‘The Immaculate Collection’ was often played – it sound-tracked the last months of his life. Stuart who lives in Scotland started The AIDS Memorial account on Instagram in April 2016. Every day, those who’ve died from AIDS are remembered via pictures and words from the people who knew and loved them, as well as first-person accounts from those who are long-term survivors of HIV and AIDS. Thank you Stuart for your inspiration and kindness. Big love Harry x

-

Maurice’s story - 19 December 1987 ‘I developed swellings in my glands and my bowel movements became difficult. I told my doctor, whose reaction was “glands, that’s nothing - feel mine. I hope you’re not becoming obsessed with your bowels.” I was sent for a blood test, but as there was no HIV test in 1982, I was told that I must have picked up a virus which had now gone. But I think that it could have been HIV as two years ago I was diagnosed as being antibody positive. Since that day, I have to thank the Sussex AIDS Helpline, from whom I had support from the first moment of the shock of my diagnosis. I very soon joined the Helpline myself - it was the only way I could cope with everything. I had to know as much as I could about AIDS. After a while I realised I wanted to work with people with AIDS, so I did a course in massage techniques, so I could offer something useful to the people I worked with. Because I have had a full life, I can’t be too sad, though I’m not ready to go yet and I’m going to put up a fight. The people I feel sorry for are the young ones who thought they had a full life to lead, and now live in fear and doubt. Today at St. Peter’s Church, I witnessed the most beautiful service of my life – a memorial to those in Sussex who have died of AIDS. Bless whoever in the Helpline who first thought of this. I shall remember it for the rest of my life, however long that might be, and I shall remember my departed friends.’ Maurice died on the 12 January 1988, quite suddenly but peacefully.

-

The Names Project AIDS Memorial Quilt was displayed at the Corn Exchange in Brighton between the 1st and 3rd of June 1993

-

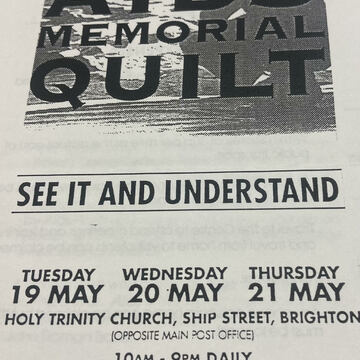

National AIDS Memorial Quilt On the 14 March 1992, Our House Body Positive & Pink Parasol held their first support group to encourage Brighton contributions to the National AIDS Memorial quilt at the Morley Street Family Centre. At this first session the film ‘Common Threads – Stories from the Quilt’ was shown, and this inspired me to create a quilt panel for my friend Andrea Philippe Regard. A series of exhibitions of the completed 6’ x 3’ panels celebrating the lives of people who died was arranged as part of the 1992 Brighton Lesbian and Gay Pride. On the 17th May (then known as Lesbian & Gay Remembrance Day - now International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia) some of the quilt panels were displayed in the Brighton Museum, and then between the 19th and 21st May the whole National AIDS Memorial Quilt was laid out at the Holy Trinity Church, Ship Street - now the home of the Fabrica Gallery. The quilt which my ex-partner Alf Le Flohic and his friend John Twoomey helped me to make, was also displayed at the Brighton Gay and Lesbian Pride celebration in Preston Park that year.

-

Paul Overton “Paul Overton died on the 21 May 1994. In true Overton style, it was one day before his birthday and in the building where he was born 46 years earlier. I am not going to romanticise about Paul now that he is no longer with us - he could be a right pain in the neck when he chose, but he was dedicated to doing as much as he could for the AIDS/HIV community in Brighton. He was the co-ordinator of Our House BP as well as sitting on the management committees of SACH and the Sussex Beacon. He was always either in meetings with the Health Authority or writing letters to organisations and newspapers when there was something printed which he felt was derogatory to those living with HIV. His time was spent tirelessly trying to improve people’s perceptions of AIDS/HIV, he contributed to ‘Inform’ regularly and was a prolific short story writer in his own right. Paul wasn’t the person I’d have chosen to be stranded on a desert island, but I did spend many evenings in his company and realised his bark was much worse than his bite! He wasn’t bothered about winning any popularity contests- he was bothered about getting his job done. I miss him.” (Words by Phil Scott - Our House BP)

-

Paul Tay 19 June 1959 - 20 May 1992 Paul was born in Hammersmith to a mother from London and a father from Ghana. I first encountered him at the University of Leicester in 1979, where we both studied. I don't recall us ever speaking, but our eyes would frequently meet as we passed each other on our bicycles. In London three years later, I spotted a very beautiful black man across the circular bar of Harpoon Louie’s in Earls Court. I plucked up the courage to ask him if he was that person from university and we became inseparable. Paul was funny and charming, with an infectious laugh; his model good looks were eclipsed by his kind and wonderful soul. His passion was driving and cars, especially vintage ones, so our weekends were spent exploring London gay bars, in his old Saab or my 1967 Triumph Vitesse. We would also spend time at the flat in Kingston-upon-Thames where he lived with his lone parent mother, the wonderful Betty. She once said we ‘might as well be engaged to be married’ considering the amount of time we spent together. To hear these words of support for our sexuality in the early 1980’ s was both unimaginable and magnificent. In 1991 Paul rang after a couple of weeks of not returning my calls; something which had never happened in our ten years together. He said, ‘you will never guess what I've got,’ and told me he had AIDS. For the next ten months I’d drive from Brighton to visit Paul at his mother’s flat and later the Broderip Ward at the Middlesex Hospital – London’s first dedicated HIV ward, opened by Princess Diana. Paul made it clear that he did not wish to discuss his illness and I respected that. One day, I asked him how he was doing, and he replied, ‘why do you ask?’ My reply ‘Well, you’re not looking your best’ made him smile. That’ s how we dealt with it, we didn't talk about it between us, and I never told any of my friends - a sign of the times. I struggle to have any pictures in my head of Paul, other than of him being happy and healthy, always so beautiful with an infectious laugh and a wonderful, beautiful soul. If he knew there was a four-metre-high great lump of bronze in Brighton named after him, he would chuckle. Words by Romany Mark Bruce

-

Paul Theobald had already been diagnosed HIV+ when we met and became good friends. He lived just opposite the Sussex AIDS Centre and Helpline (SACH) with his partner Terry Morgan, and I lived nearby. Paul was worried that there were no weekend services for people with HIV, so he decided to start group meetings at his flat on a Wednesday. Back then SACH had a telephone helpline seven nights a week and a buddying service staffed by volunteers like me. There was also a small BP group, but volunteers were not allowed to go unless invited. I was fortunate enough to be invited alongside a paid worker we called ‘mother.’ Open Door provided lunch Monday to Friday and I cooked vegetarian food there every Tuesday. Paul’s meetings were popular because he was very charismatic, and soon something bigger was needed, so Sunday lunches were started in different homes each week, alternative therapies were introduced, and it wasn’t long before Our House Body Positive was born in 1992. Paul had it registered as a charity and premises above the old fruit & veg market in Circus Street were found. Paul was the first Chair we had, and I started fundraising with bric-a-brac stalls in the summer. I remember one Easter we put an advert in the Evening Argus for unwanted bits & pieces. I went down to Paul’s flat early one Saturday after stopping to buy 30 bunches of daffodils with our own money. We then drove all over to the homes of people who’d donated, and as people gave us their items, we wished them Happy Easter and gave them daffodils as a thank you. Paul worked very hard for OHBP and after a while it started affecting his health, so he stepped down. After his relationship with Terry ended, he decided to move back to London into a ground floor Flat in Islington where I visited a couple of times. His health improved, and he was soon back to the Paul we all knew. Sadly, we lost touch until 2004 when he phoned me to say he'd like to come to Brighton for a few days if I promised not to tell anyone. He said he'd let me know when he was coming, but alas that's the last I heard of him.

-

I first met Paul Woodward (also known as Morticia) at the Our House Body Positive premises in Circus Street. Paul’s partner was also called Paul, so we called him Kim to avoid confusion. They were always together and came to OHBP most days. It was handy for them as they'd recently moved into a flat nearby on Ashton Rise. We became good friends because Kim was a hair stylist, and I needed a new one as the person who’d been doing my hair had crossed the rainbow bridge. Paul and Kim always came to my flat together. Paul wasn't 100% well and he’d had about eight operations for a collapsed lung at different times. Despite this he continued to chain smoke which really didn't help. The three of us did a Millinery course together after I said I was fed up with the gay community making better hats than me. We also used to go out a lot together as they had a car. They took me on holiday to a farm in Somerset once as a birthday present and lavished me with some beautiful gifts. Paul was not very well on holiday, but he still insisted on doing the cooking despite his poor sight which was deteriorating rapidly. I suggested he took up pottery so he could sense things and learn to feel with his hands better which he seemed to enjoy. There was a time when I was over in Rhodes seeing my daughter which coincided with a cruise they were on. Their ship docked at Mandraki Harbour for the day and I met them to show them around the old city. By this time Paul was using a white stick. As we strolled along with our arms linked, everyone seemed to be staring which made us all feel really uncomfortable, but we still had a memorable day. I heard that Paul crossed the rainbow bridge in 2008. Sadly, I’d lost touch with them as I was in Kenya by then, but I did send Kim a letter of condolence. Words by Avee Isofa Holmes

-

Philip’s panel was part of the AIDS Memorial Quilt display in Washington in October 1992, and I went with mum and the UK gang for a week. His panel came up on CNN news later that day picked out from thousands. Philip was from Bootle in Liverpool, and we started going out when I was 17 and he was 21. He was insulting, cheeky and funny, blind in one eye, five foot one with size 3 feet, but his mouth made up for his stature. I am always intrigued by people who take the mick out of me so I was hooked. We moved to London in 1978, and he worked at the post office on the King’s Road. He was diagnosed HIV+ in 1985 and with full blown AIDS in 1987. Australia was our last chance of a holiday together as he was beginning to get weaker. He loved music, especially Philadelphia soul and Helen Reddy. He loved laughing and would tell people their friends had died for a laugh - weeks later they'd bump into them on the tube...ha, he was a monkey. Him and my family got on great and he was my first proper bloke to go out with. We had a beautiful Dr in Hackney called Dr Feder. He tried all kinds to help at a time when hospital staff treated us like the plague. I used to tell people he had cancer when they asked, because it seemed mild in comparison. It all seems another life away, but it's always just under the surface because it was a massive thing for us to go through. I was 24 when he was diagnosed and it took me about five years after Philip died to feel something like me again, but I'm sure he’s fine now in Oz. He's had a quilt panel, a painting and Australia - that's your bloody lot...ha xxx Words by Gary Sollars 'My partner Philip Munro. Died 13.1.89. Aged 34' a painting by Gary Sollars On a hospital bed bathed in an ethereal light lies a man who has just died. Weeping by his side are two women. Another man is kneeling with his arms stretched across the mattress. Two more men, their bodies naked stride away. From the hand of one of them flutters a red ribbon, the symbol of AIDS awareness. The painting earned Gary Sollars the overall prize for outstanding work at the Sussex Open art competition of 1996. It’s a deeply personal work which Gary saw as a final stage to the sorrow he experienced after losing Philip to AIDS after 13 years together. “The bed scene kept coming up in my head,” he said. “I wanted to do something about being gay, and the obvious subject was the loss.” The first stage of Gary’s grieving process was to scatter Philip’s ashes over Ayers Rock in Australia. “We went on holiday to Sydney in 1987, and coming back we had to choose between seeing Disneyland or Ayers Rock. We went to Disneyland - I wanted Philip to have had the experience of being in both places.” Gary went on to make a panel for the UK AIDS Memorial Quilt which depicts Ayers Rock with footsteps leading the way. It was exhibited alongside other local panels during Brighton Lesbian & Gay Pride in 1992. “You don’t realise it, but the bereavement process takes a long time. You’re think you’re OK for a while, and then something triggers it off again.”

-

Reflections of an Unsung Hero Reflections of an Unsung Hero was a solo performance created by Robert Pacitti, directed by Colin Schantz and commissioned by Aputheatre (AIDS Positive Underground Theatre Company) to cherish the work of Graham Wilkinson. Playwright John Roman Baker was so impressed by Robert’s performance of ‘Lust’ during his second year at Art School in 1990, that he approached him to create a performance to honour Graham, and gave him full copies of Graham’s diaries to work with. The commission asked for a radical live performance that responded to the content of the diaries, Graham’s Gay Liberation Front and extensive AIDS activism, and his significant lifetime legacy fighting for change. Because Graham had lost his sight, Robert wore an eye mask and travelled around Brighton on the bus to immerse himself in the role. The play was rehearsed at the Sussex AIDS Centre and Helpline in readiness for the 1991 Brighton Festival, but was nearly de-railed when Gavin Henderson, the Brighton Festival director, pulled the play from the programme due to its subject matter and the theatre company name. Lindsey Kemp was one of the festival headliners that year, and when news reached him that the play had been removed from the programme, Robert was asked to meet at his hotel. When Lindsey heard the full story, he gave Robert £500 in cash so that the play could go ahead, and had it reinstated in the festival programme. The play was performed at the Marlborough Theatre on the 26 May 1991.

-

Roy Davies was by all accounts a lovely man and a brilliant fundraiser. He lived in a couple of cottages in Kemptown just down the road from his friend David Raven’s guest house. As well as helping to raise cash for Our House Body Positive, he also sat on the committee of the Rainbow Fund which back then raised money for people living with HIV/AIDS through entertainment events. Roy’s many show biz contacts proved invaluable when putting together countless shows. His own fancy dress parties, like his 60th birthday party at the Royal Albion, were also legendary. Roy was a quiet man, and despite being positive he rarely talked about his condition and didn’t use the services on offer. Eventually the virus took its toll, and he became very drawn and simply faded away.

-

I met Shaun at a Body Positive Group meeting at the Sussex AIDS Centre and Helpline (SACH) which I’d been extremely privileged to be invited to. We also met sometimes at Open Door where he sometimes went for lunch. Shaun was a quiet person who kept himself to himself most of the time, but he could be quite outspoken if he felt something was wrong. He was helped a great deal by his partner Nick who was a volunteer at SACH and always very smartly dressed. Shaun was a regular at the Bulldog pub but didn’t talk much about his personal life. Words by Avee Tsofa Holmes

-

Simon Mckenzie Dwyer was a curious fellow. A pub brawler and a football hooligan. A Plymouth Argyle supporter with a tender soul and ferocious intellect. Raised a Catholic, abused and beaten by Christian brothers, he grew up feeling anger, guilt and shame but found David Bowie and a way out. I first met him when I was 17 and an understudy at Chichester Festival Theatre. I had just bought a red dress and he was stage crew watching the rehearsals. He saw me and said “I’m going to marry that girl in red.” I grew up in a small village in West Sussex, sheltered and naïve. I followed him to a squat in an enormous council estate in Poplar, East London. He started a fanzine in the late 70s called ‘Rapid Eye Movement’ and I was introduced to his friends who were musicians, writers, poets, performance artists and one glorious heroin addicted painter called Nicky Slagg who lived in the underbelly of a derelict Wapping warehouse. I remember stapling the fanzine pages together. The music magazine Sounds picked up on Simon’s interview with Crass who had refused interviews with the mainstream press. Like so many others, Crass co-founder Penny Rimbaud respected Simon and agreed that Sounds could re-print the article. Sounds then employed Simon as a music journalist. Much to my excitement he reported on Adam and the Ants and all the punk bands. He also went on a Belgium tour with The Cure, but his passion was for sub culture and his own philosophies on life and increasingly death. He poured his heartfelt ideas into his own Rapid Eye project and always ahead of the game he began to amass a following, some less savoury than others. Years after his death I found a letter that was postmarked Waco, Texas – a rambling missive from David Koresh. In the late 80s he started to feel unwell, lost weight and developed strange rashes. He took a HIV test in a private hidden clinic in London. The results were ‘unequivocal’ and we knew what that meant. He was officially diagnosed in 1992 and placed in the wonderful care of Dr Martin Fisher. He continued with Rapid Eye and writing for different projects with Genesis P-Orridge. Gen had been a dear friend for many years and felt the loss of Simon very deeply. Derek Jarman and Gilbert and George also supported him when his health began to deteriorate. Simon had several admissions to the rather grim Ward 6 in Hove (now a block of luxury flats – I wonder if the owners know the history). He was pumped full of toxic agents that were well intentioned and supposedly maintaining his CD4 count and reducing the viral load, but they had horrendous side effects. He had one drug that induced psychotic episodes during which he’d ask me to leave the house and hide the knives because he feared he might “butcher the cats.” At this point, for my safety, he was admitted to the amazingly beautiful Sussex Beacon where he decided to stop taking the drugs. He spent the last six months of his life there. The staff there were angels, always loving and kind. Simon used to smoke at least 40 Dunhill International a day and made so many burn holes in his bedding that they had a special rotating set of sheets and duvet covers for him. He fell into a loving, cherished morphine induced slumber. The last time he woke up, he asked me for a fag which I held to his lips. He savoured two drags and then slept gracefully. A few days later he died in my arms, clean and fresh and sweet as a daisy. When the doctor, Jonathan Wastie, came in to certify the death he kissed Simon on the forehead and said “farewell darling.” I said “sail safe dearest with Peter our son who was born sleeping in this world but reaching out to embrace you in the next.” Words by Fiona Dwyer Obituary written by Paul Cecil for The Independent – published 28 October 1997. Simon McKenzie Dwyer, writer and editor: born Salisbury, Rhodesia 28 November 1959; married 1982 Fiona Pritchard (one son deceased); died Brighton, East Sussex 26 September 1997. Simon was an extraordinary young man who established himself as one of the leading commentators and contributors to, the artistic and creative subculture of the last two decades. A writer first and foremost, he focused his work through the magazine he first conceived in 1979 and named Rapid Eye. The youngest of three sons, Dwyer was born in Salisbury, Rhodesia, in 1959 but moved to England a year later, when his family returned, moving around the country before settling in Plymouth, where Dwyer attended, somewhat reluctantly, the local schools. He left Tavistock Comprehensive shortly after his 16th birthday. This was the time of punk which turned many heads away from convention and towards the exploration of the alternative and improbable. It was precisely into this area of burgeoning cultural expansion that Dwyer focused his energies. His understanding of the possibilities awakened by rejecting hierarchical and formal society was already gestating, as was his willingness to embrace the art and performance of transgression. In 1978 he moved to London and began, in the tradition of punk writers, developing his own fanzine, Rapid Eye. The first issue which hit the streets in 1979, included a feature article on anarchist band Crass which was quickly picked up by the music paper Sounds. Dwyer established himself rapidly as a regular contributor to Sounds, interviewing the famous, the soon to be famous, and – as is inevitable in an industry that so vicariously promotes and demotes – the once famous and the never will be famous. This eclectic mix served mainly to reinforce in Dwyer the belief that status is the least relevant concerns and that it is the human level, and creative integrity, that above all marks out the true artist. By 1982 Dwyer had moved to Brighton, and it was in that year that he married Fiona Pritchard. It was soon after this that sadness struck their lives, with the death at birth of their only child, Peter. The world of commercial journalism became ever less attractive to Dwyer and he moved from it to that of interior design, joining Rhodec International. Alongside this work, he continued writing, developing Rapid Eye into an increasingly lavish exemplar of fanzine art. Indeed, the famous “Black” edition which he produced in 1986 has since become a sought-after collector’s item. However Rapid Eye as a concept, despite its plaudits, had for him never reached its potential. Calling in favours from friends and contacts he had made through his earlier work, he set out to produce the ‘zine to end all ‘zines: a coffee table edition, massive in scope, scale and vision. And how those favours rolled in: Andy Warhol provided the frontispiece; William Burroughs sent three pieces of writing, “And His Name was Rover”, “The Johnson Family” and the “Fall of Art”. Kathy Acker, Genesis P-Orridge and Colin Wilson also contributed to the volume, as did Derek Jarman. Alongside this galaxy of stars, Dwyer included, with no less care or column inches, a raft of unknown writers with specialisms ranging from conspiracy theories to foot-binding. Over a year in the making, Rapid Eye 1 (1989) proved to be inspirational, in the words of the New Musical Express “a veritable treasure-trove of mind-activating information. Penetrating, comprehensive, most illuminating.” With the task of the first “real” issue behind him, Dwyer and his wife transported their life to America. They were there to develop Rhodec’s North American presence, but inevitably spent the best part of their year travelling across country. It was this, certainly, that provided the inspiration for Dwyer’s greatest exploration of his journalistic skill, a text of 100,00 words, “The Plague Yard: Altered States of America”. It was on their return to England in 1991 that Dwyer learned that he was HIV positive. While coming to terms with the diagnosis he completed “Plague Yard” and concluded a commercial deal with Creation Books for Rapid Eye. The idea of publishing “Plague Yard” as a book was floated. Those who read the text found it astonishing: the art of the travel writer re-configured into a plea for cultural freedom, with the punk aesthetic not only intact, but validated as never before. Focusing as much on low art as high, the piece shows Dwyer to be much at home with the disposed idealist as with the art-elite glitterati. But Dwyer for all the praise heaped on him, remained true to the spirit that had long driven him, and declined the offers. “Plague Yard” was not to be used to announce his elevation in the literary field, instead it was to exist, and stand or fall on its merits, alongside many other pieces, simply as a contribution to Rapid Eye 2. By 1993 the debilitating effects of HIV were becoming an unavoidable presence in his life. Minor ailments mounted up, fatigue set in, and work began on the third and final volume of Rapid Eye. The centrepiece of the volume is a startling piece, by Dwyer himself, on the art of Gilbert and George who offered the use of their painting “We” as the cover. Rapid Eye 3 was launched in London in 1994.

-

I met Stephen in a Kemp Town gym, and we became better acquainted in the jacuzzi. His partner was Omar, known to his friends as O. They became good friends of mine, and their large flat on Preston Park was always open to me and other friends. They both had a good eye for interior design and enjoyed a comfortable life. Stephen and I used to go swimming regularly at the Eastbourne leisure centre, stopping off at my house near Lewes on the way back. Somehow, I lost track of Stephen and O for a couple of years, but we reforged our friendships, stronger than ever, after we all were living with HIV. They separated at the start of the 1990’s, and Stephen died from Pneumocystis Pneumonia (PCP) in Ward 6 of Hove General Hospital in 1994.

-

Sussex AIDS Centre “We held the first Brighton and Hove public meeting on AIDS in 1984 at offices in Lansdowne Place, Hove. Graham Wilkinson and I split the small cost of hiring the room and invited someone from the recently formed THT to come along and explain what they were doing in London. Both Graham and I had joined THTs small Social Work group which met at their original tiny offices in London – at that time only consisting of a couple of rooms. So, it was at this first public meeting that a handful of us volunteered to set up the Sussex AIDS Helpline. We knew the person who at the time managed the Well-Women Clinic above a shop on the corner of Western Road and Waterloo Street in Hove. They very kindly agreed to let us use their offices in the evening when they were closed and allowed us to use a telephone line for free. Graham and I both worked together as Social Workers in the Hanover Team based opposite St Peters Church, and we managed to get permission to use our offices in the evening for training and support groups. As professional social workers we were able to put together a training programme for the early volunteers to help handle phone calls. Graham or I would either take the calls ourselves, or be there as support for the other volunteers. For the first 2 years Sussex AIDS Helpline got no official funding. We managed to get by with volunteer time and effort, meeting in each other’s homes, raising awareness in pubs and clubs, and by borrowing facilities and resources from the Well Women's Clinic and Social Services Hanover Team. A couple of years later we became the Sussex AIDS Centre and Helpline.” Clive Stevens